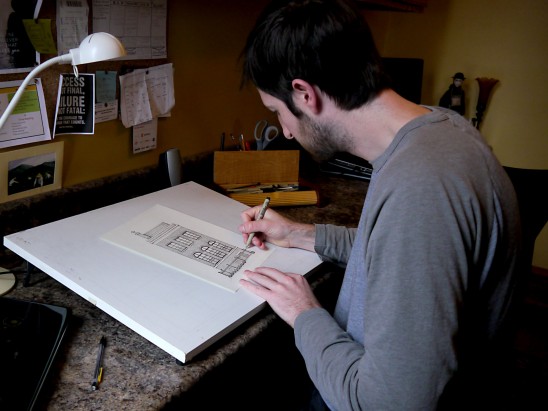

Molly McGrath is a laser-cutting artist who marries her architecture training with her love for geometric shapes and bright hues. Molly’s statement art pieces are known for intricacy and precision, yet words like “lively” and ”fun” still come to mind when you see them. I visited Molly’s lovely studio in the heart of The Mission in San Francisco and it wasn’t a surprise that her open space mimicked her artwork’s aesthetic – flashing lots of playfulness with even more color. Her studio held lots of character, from her personable knick-knacks to her hand painted geometric doors, I simply couldn’t focus on just one thing. Natural light flooded in, her laser cut designs peeked out from drawers and vignettes, and her desktops were scattered with signs of production. I felt like I was standing in the middle of a real life Pinterest board titled “Interior Eye Candy.” It was clear that Molly built a home away from home – a space that was truly hers to the very core.

Creatives often try their best to limit distractions in order to stay focused on their craft. Yet it was procrastination for Molly that ignited the initial spark for her small business. As Molly told me, “I used a laser cutter extensively in architecture school – making models mostly out of birch plywood. I have always made jewelry and one day, while procrastinating, I decided to make some earrings on the laser cutter. That was the beginning!” Read about Molly’s friends Larry and Lola, what quote keeps her inspired, and her current obsession to perfect her craft!